The State of Mortgage Lending

Teraverde is a leading provider of high-end mortgage solutions, offering innovative, flexible mortgage consulting and related software solutions to clients. Not only has the company worked with scores of clients– leveraging their current operations to provide custom solutions that help them achieve their long-term financial goals, but also Teraverde has productized several solutions and services that have been able to help hundreds of clients achieve operational and production excellence. The company’s CEO James M. Deitch talked to us about how he sees the state of mortgage lending.

Q: Jim, you’ve been a lender for 25 years, and you are in your tenth year as an advisor to the industry. What do you see as coming next?

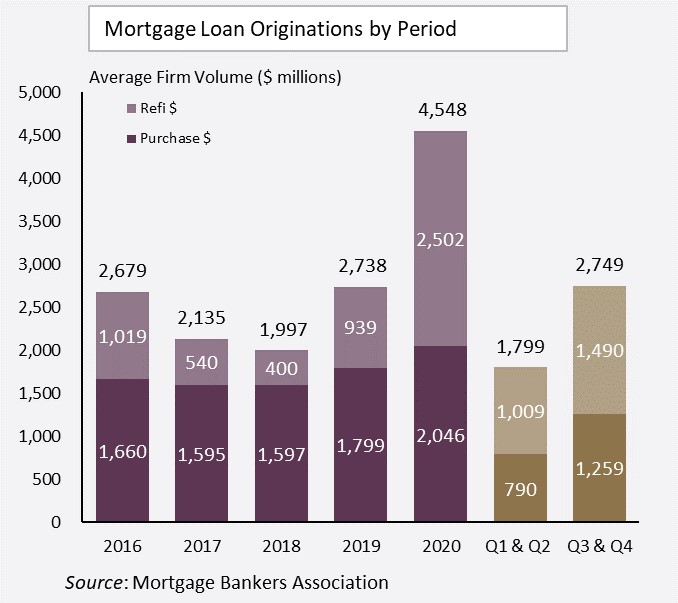

JAMES M. DEITCH: The industry is cyclical, both in terms of production volume and in terms of risks. First, production. We’ve seen the highest run rates ever, hitting about a $5.5 trillion run rate (annualized) in the second half of 2020. This run rate rivals the 2003 and eclipses it by at least $1 trillion. Production volume will fall to about $3.3 trillion in 2021, according to MBA forecasts. That’s still a great year.

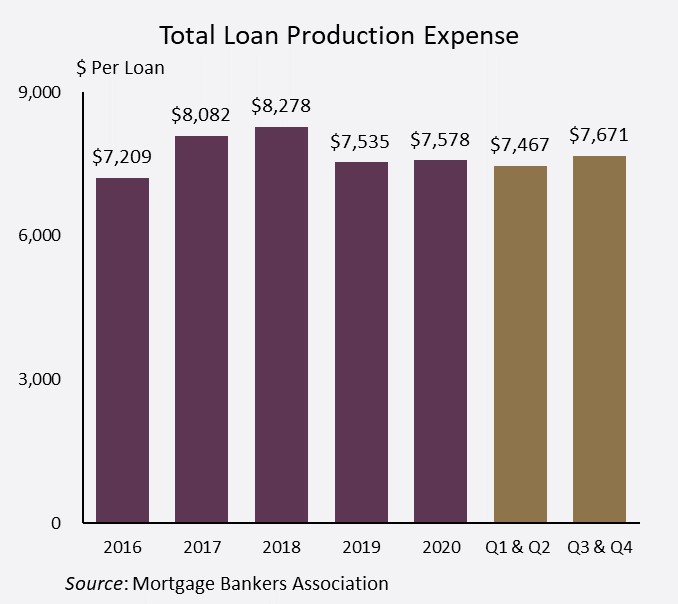

The amazing thing to me is that there were no economies of scale realized. It cost about $7,500 to close a loan in 2020, similar to costs from 2016-2019. This is unsustainable long term. As margins compress, the pressure on profitability will increase.

We’ve seen many of the large privately owned IMBs go public to de-risk their owners and take money off of the table. This will put downward pressure on stock prices, and close the door to those that didn’t pull the trigger quickly on the IPO window of opportunity.

The urge to merge will increase for IMBs. Whether this is beneficial will be highly dependent on the cultures and leadership capabilities of those involved.

Q: Can you talk about the risks you see?

JAMES M. DEITCH: The key challenge for lenders will be the risks of having profits from the last fifteen months clawed back from them. There are many ways to have claws grab your profits. The first is failing to right size when profitability comes under pressure. You have to quickly identify and cut your weakest links. It’s hard to do that emotionally, but I’ve never run across an executive that told me, “I fired someone too quickly.” It’s usually, “What took me so long?” So, whether its loan reps, operational employees or branches, move on the weakest links quickly.

The second major risk is regulatory. The new Administration has wasted no time transferring costs onto the private sector. COVID foreclosure moratoriums, withdrawal of the ‘good faith accommodations’ defense from COVID related disruptions. FHFA directives on cash window and loan mix sublimits. Dave Stevens, former CEO of the MBA, once commented that the industry earned $300 billion all in from 2002 through 2008, and had much of it clawed back in fines, ‘restitution’, repurchase settlements and legal fees. Don’t think it can’t happen again.

Q: What should lenders be doing about mitigating these risks?

JAMES M. DEITCH: Risk mitigation is essentially proactive action. Make sure loan files are complete, accurate and document decisions, particularly regarding collateral valuation and income determination. I performed expert work for RMBS and repurchase litigation on about $25 billion of loan principal. The common themes were losses pushed back to lenders for lack of complete documentation. Sloppiness. Based on what I’ve seen in loan files, we could have the same issues again.

Q: Haven’t the GSEs taken steps to reduce repurchase risks to lenders?

JAMES M. DEITCH: One could have that view. I’m more cynical, as the GSEs are essentially run by competing political camps. We’ve seen how COVID relief costs, servicing advances, etc. have been pushed back onto private enterprise. The deficits and voracious appetite for federal and state spending will make our industry prime targets for regulatory and GSE attempts to view lenders as sources of cash. Why? Because that’s where the money is.

Q: You often speak and write about what we could learn from other industries. Any current thoughts?

JAMES M. DEITCH: Sure. One is the age old issue of originator compensation. A CEO friend of mine said, “A lot of us have the stones to change the business structure and compensation. I just don’t want to be first to reduce compensation to originators.” I understood. The first one through the door often gets roughed up pretty well.

This though takes me back to discussions with Billy Beane, an executive with the Oakland Athletics Major League Baseball team. Shortly after the movie “Moneyball” had premiered, Billy gave a presentation at the MBA’s Chairman’s Conference to a small group of CEOs. His talk recounted how he had to let highly paid, ‘big name’ players go because of compensation constraints for the team.

Beane spoke about finding undervalued baseball players who could work in a collaborative manner so that the A’s could compete with teams that had “star” players. Billy’s goal, in fact, was to develop a team that could compete and win against much better-financed opponents without any big name, big pay ‘stars’ at all.

I happened to sit next to Billy for lunch after his presentation and took the opportunity to probe more on the data-driven strategy that Billy had implemented at the Athletics. He described the strategy: “It’s about winning games at the least cost. We’re a small market team and can’t afford to pay the salaries of large market teams. But we can still compete and win as long as the cost of winning a game fits our budget.”

Beane’s strategy worked because baseball teams had accumulated a vast amount of data on every player’s at-bat performance, fielding performance, tendencies, etc. This data, however, was not used by teams in the same way as Beane used it. The analytics done for Beane provided insight into what performance factors into games (‘on base percentage’), and how one could obtain players that were not viewed as ‘stars’ but had good ‘on base’ production while being paid modestly.

The same opportunity exists in mortgage lending. Many companies pay originators on volume. The lender don’t leverage all of the other data generated in the origination process. Cost of cures. Number of operations touches. Loan type and purpose mix. $50 million of jumbo is not nearly as profitable s $50 million in govvies. But lenders often pay originators on volume, with only a glance at a balanced scorecard of volume, margin, cures, concessions, pull through and turn time. My team members built that scorecard as a bolt-on to an LOS. Huge opportunity to increase profitability for a lender.

Q: Why not more of a focus on profitability?

JAMES M. DEITCH: First, it’s not in our industry DNA. We’re comfortable with volume as an analog for profit. But that is a very inaccurate method of evaluating performance. Second, Dodd-Frank transferred compensation risk onto lenders to prevent steering so the management of originator compensation is often binary – I hire and keep them, or I let them go. Third, the data to measure originator profitability is hard to harness.

Q: Why is it hard to harness?

JAMES M. DEITCH: One needs a model of what is actual originator profitability. It’s pretty straight forward. I prefer “Contribution Margin. The definition is Gain on Sale, SRP, all lender fees collected, less concessions, cures, lender credits and compensation to the originator. That measures exactly what job an originator does, and how well they do it.

The originators’ job is to bring in quality loans that close quickly, while collecting all revenue and fees without concessions or cures and achieving volume and customer satisfaction targets. Contribution margin measure this. It’s like the ‘on base’ percentage that Billy Beane speaks about.

Q: Have you solved some of the data accessibility issues?

JAMES M. DEITCH: We offer a solution called Coheus. Out of the box mortgage business intelligence that incorporates how successful lending executives think about measuring performance. Contribution margin on originations, for example. Out of the box with Coheus.

Q: What else are your thinking about?

JAMES M. DEITCH: Profitability and disruptive forces. First, profitability. I think a lot about minimizing the cost per loan and/or maximizing the profit per loan. When I ask a mortgage banker about their business statistics, the first quantitative description that they mention is the dollar volume of originations. A natural answer, since that scopes out the basic scale of the operation. But volume is not a description of the lender’s profitability, health, cash flow, or long-term viability.

It’s not an industry secret—many mortgage bankers are enthralled by volume. Entry into the top 100 or top 10 lenders is an aspirational goal for many, and it has set the standard of success for decades. Is this devotion to volume over profit beneficial to the mortgage banking industry in the long run?

Some lenders view volume as a metric of success. “We have 7 of the top 100 loan officers in the country.” This is a metric based on volume, but are these loan officers profitable? When I ask a CEO about company profit, the answer is usually, “We’re better than peer.” Statistically, half the time this may be true. The other half of the time, it is not. Not everyone can be “better than peer.” C level executives of lenders don’t seem to focus on profit as much as other industries.

Second is disruption. Margins in the last 15 months have been very high. This is great on one hand. But fintech and other competitors will see lender margins as their opportunity. Banks used to make a lot of money on car loans to their customers. It’s now all indirect auto paper, as the auto dealers use financing as a strategic sales tool and profit center. Banks had their lunch eaten.

Eating a lender’s lunch is on the minds of non-traditional lenders, fintechs and large players like Amazon. Not sure who will successfully challenge the current status quo. One should be thinking about how to become a low cost, high quality producer of mortgage loans should be on everyone’s mind. Because $7,500 per loan is unsustainable.

INDUSTRY PREDICTIONS

James M. Deitch thinks:

First, the last quarter of 2021 and most of 2022 will be a much different economic, regulatory and political environment. Earning a profit on production will be much harder, so prepare now to work on becoming a low-cost producer.

Second, keep an eye on inflation metrics. I think the surprise will be on the upside of inflation data. Inflation hits first time buyers with a higher home price and higher interest rates. Be prepared with tools to help buyers through these issues.

Lastly, expect the GSEs and FHA to be very aggressive with loans that do not perform, regardless of what their ‘policy’ may be. Since conservatorship, the agencies are run on a political basis, and requiring any draws from the Treasury department won’t be welcome. So expect costs of forbearance, servicing advances and credit losses of any significance to be pushed back to the private sector. That means lenders. Start your defense now, and clean up data, underwriting narratives, collateral evaluation etc.

INSIDER PROFILE

James M. Deitch is an entrepreneur, having founded two national banks, several mortgage banking ventures, and four technology-oriented companies. He currently serves as co-founder and CEO of Teraverde group of companies. Teraverde is a professional advisor to financial services companies. Teraverde helps banks and mortgage bankers achieve greater profitability, streamlined operations and process improvement.

The Place for Lending Visionaries and Thought Leaders. We take you beyond the latest news and trends to help you grow your lending business.